by Jonathan Booth

“We saw two swimming past our canoe the other day as we came to shore!”

“Yes, we saw one over towards the mangroves not so long ago…”

“There was one in our net near the big river…”

Scientists love having a mystery to solve and gathering clues to find out if something is real or not. Since January 2019 my organization, the Wildlife Conservation Society, has been collecting evidence to confirm whether highly endangered sawfish and their relatives — the wedgefish, guitarfish and giant guitarfish (collectively and affectionately known as “rhino rays”) — live in the coastal waters of New Ireland Province, Papua New Guinea.

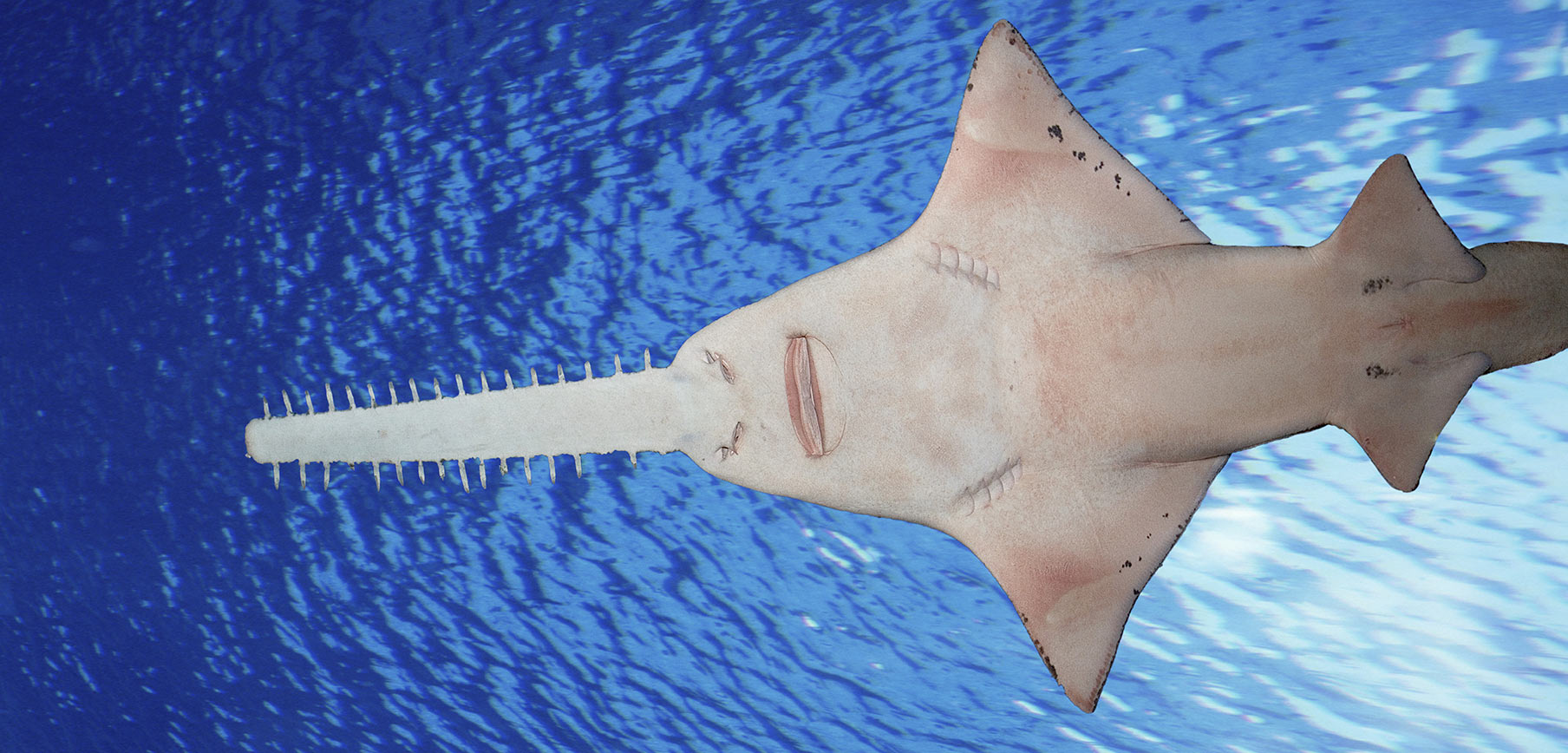

Sawfish and their rhino ray relatives — all cousins of sharks — are some of the most threatened species on Earth due to their slow growth, vulnerability to capture in fisheries, and high value in international trade. Recent studies indicate that Papua New Guinea is (together with northern Australia and the southeastern United States) one of the last few strongholds for sawfish populations, making the country a global priority for shark and ray conservation.

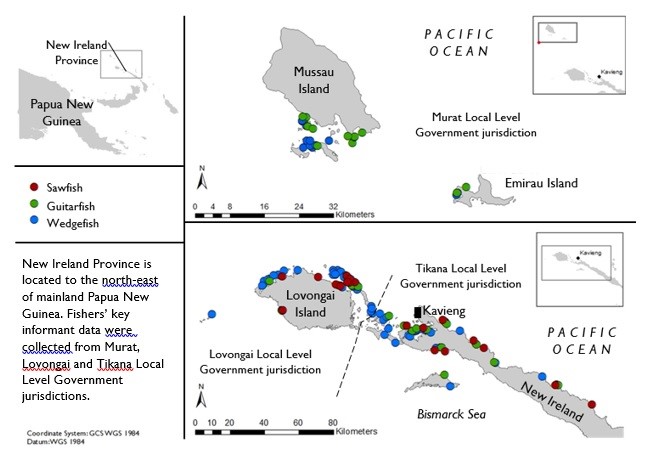

Currently sawfish and rhino rays have been well documented along the southern shores and adjacent river systems of Papua New Guinea, and also in the Sepik River, which drains into the Bismarck Sea on the northern coast of the mainland. Sawfish have also been documented in several other provinces in the country, yet no official records exist in New Ireland Province.

Until now.

A Unique Site

The southwestern Pacific nation of Papua New Guinea is known for its renowned biodiversity, much of which lives nowhere else in the world. But that amazing animal and plant life is often both understudied and under threat.

This holds true in New Ireland.

The many islands of New Ireland Province, located in the Bismarck Archipelago, support coral reefs, mangroves, estuaries and tidal lagoons — typical habitats for rhino rays and sawfish. Some 77% of New Ireland’s human population also lives in the coastal zone, where they’re highly reliant on fish and other marine resources for food, livelihoods and traditional practices. Local communities also own most of this coastal zone through customary tenure systems, which may have been in place for centuries.

Human pressure, including population growth, could threaten potential sawfish and rhino ray populations unless sufficient management is in place — but local cooperation will be key to such action.

Surprising Surveys

Over the past year and a half, WCS has conducted interviews in New Ireland’s coastal areas. Part of the interviews involved showing images of each sawfish, wedgefish and guitarfish species, allowing respondents to identify what they saw. To date residents from 49 communities reported that they had seen sawfish and rhino rays in their local waters. There were 144 separate sightings reported by 111 respondents, which comprised 23 sawfish, 85 wedgefish and 36 guitarfish and giant guitarfish. Roughly half the respondents stated they had seen sawfish or rhino rays either often or sometimes.

When asked if the animals were targeted by local fishers, more than half the respondents said no: The animals were mostly caught accidentally. Only 9% of the sighted sawfish and rhino rays were reported to have been purposefully caught.

Respondents also provided information on where, and in what condition, they had seen the animals: 77% were seen alive, 10% at the market and 2% entangled in nets.

The results suggest that while sawfish and rhino rays are in the region, they are not a key fishery commodity, which is promising news for developing conservation approaches.

Further Evidence Needed

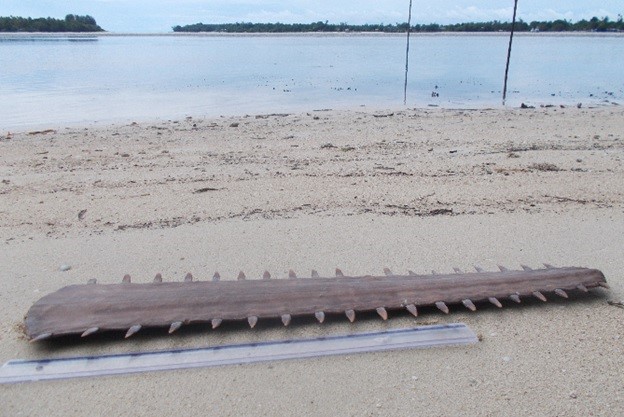

While physical and objective data has been lacking — I’m still waiting to see one of these animals in the water, myself — we have confirmed evidence of two large-tooth sawfish (Pristis pristis) in the region (two sawfish beaks, also known as rostra, have been found in community villages since this study began), and we’ve received reports of additional sightings.

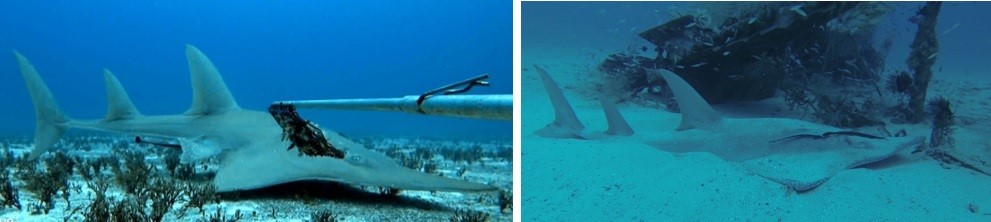

WCS also conducted baited remote underwater video surveys (BRUVS) in 14 locations in the region in 2019-20, following a 2017 BURVS deployment by FinPrint in western New Ireland Province.

Collectively the BRUVS documented 13 species of sharks and rays, including wedgefish (which have also been photographed by local dive operators), but no sawfish.

But with that success, we’re expanding our search. Over the next 12 months, a further 100 BRUVS will be deployed in areas with a sandy seafloor, where wedgefish and giant guitarfish often rest. Because sawfish typically live in estuaries — where water is often murky — BRUVS will not work due to the poor visibility of the water. In these areas gillnets that have been carefully positioned in river outlets by trained local community members will be monitored for sawfish that may be present. If any sawfish are present in the nets, they will be documented and carefully released.

Opportunities for Conservation

Despite the vulnerability of sawfish and rhino rays — with five of the ten documented species in Papua New Guinea classified as critically endangered — there are currently no protection laws in place. However, since 2017, WCS has worked with over 100 communities in New Ireland Province to establish the country’s largest network of marine protected areas.

The MPAs have been developed through a community-first approach, with extensive local outreach, engagement and education. In that way WCS has been actively informing local residents about the biology, threats and management opportunities for sawfish and rhino rays. We anticipate that new laws to protect and manage these endangered animals will be incorporated into the management rules for the new MPAs.

While the mystery as to whether sawfish and rhino ray populations are alive and well in PNG has largely been solved, they are still rare and in need of additional conservation efforts. We hope that this work will help bring awareness and conservation action to these highly threatened species — and make sure they don’t become mythical creatures of the past.

Source:

The Revelator